A Look Back: Three Teens Rescued From Abandoned Mine

posted

Last summer three boys set out for a bike ride. When they didn't return, their afternoon adventure turned into a 16-hour multi-agency search operation at the Neda Iron Ore Mine in Iron Ridge, Wisconsin.

The Madison Fire Department's Heavy Urban Rescue Team was among those who helped find them. Here's their story…

Just Another Sunday

It was a warm July afternoon when 16-year-olds Tate and Zach and 15-year-old Sam hopped on their bikes and rode off for what was supposed to be just another summer adventure. Along the way, they stopped at the nearby Neda Iron Ore Mine, a site known to attract curious kids who like to explore, even though the mine has been closed to the public for over seven decades†.

With cell phone flashlights in hand, the boys traversed the dark recesses and rugged terrain of the abandoned mine. Then, their cell phones died. With no light source to guide their way out, the boys took shelter inside the mine.

Their parents grew more distraught when calls to their cell phones went straight to voicemail. That evening, the Dodge County Sheriff’s Office began a search of the area and ultimately found the boys’ bikes outside the Neda Mine at 2:40 a.m. Monday†.

As deputies continued exploring all possibilities, including the chance of a child abduction†, the Iron Ridge, Woodland, and Neosha Fire Departments responded to the mine to begin searching the intricate network of pathways and tunnels.

Madison HURT Responds

Local authorities searched for hours without any luck and eventually determined more help was needed. At 3:45 a.m., the Madison Fire Department’s Heavy Urban Rescue Team (HURT) was asked to come up to Iron Ridge.

In the pre-dawn hours, the ten-person special rescue team based at Fire Station 8 assembled and headed to the Neda Mine, the farthest the team had ever traveled for a mutual-aid response.

The HURT arrived at 5:00 a.m. and paired up with members of local fire departments. Together they formed Interior and Exterior search teams consisting of two Madison HURT members and two local firefighters each.

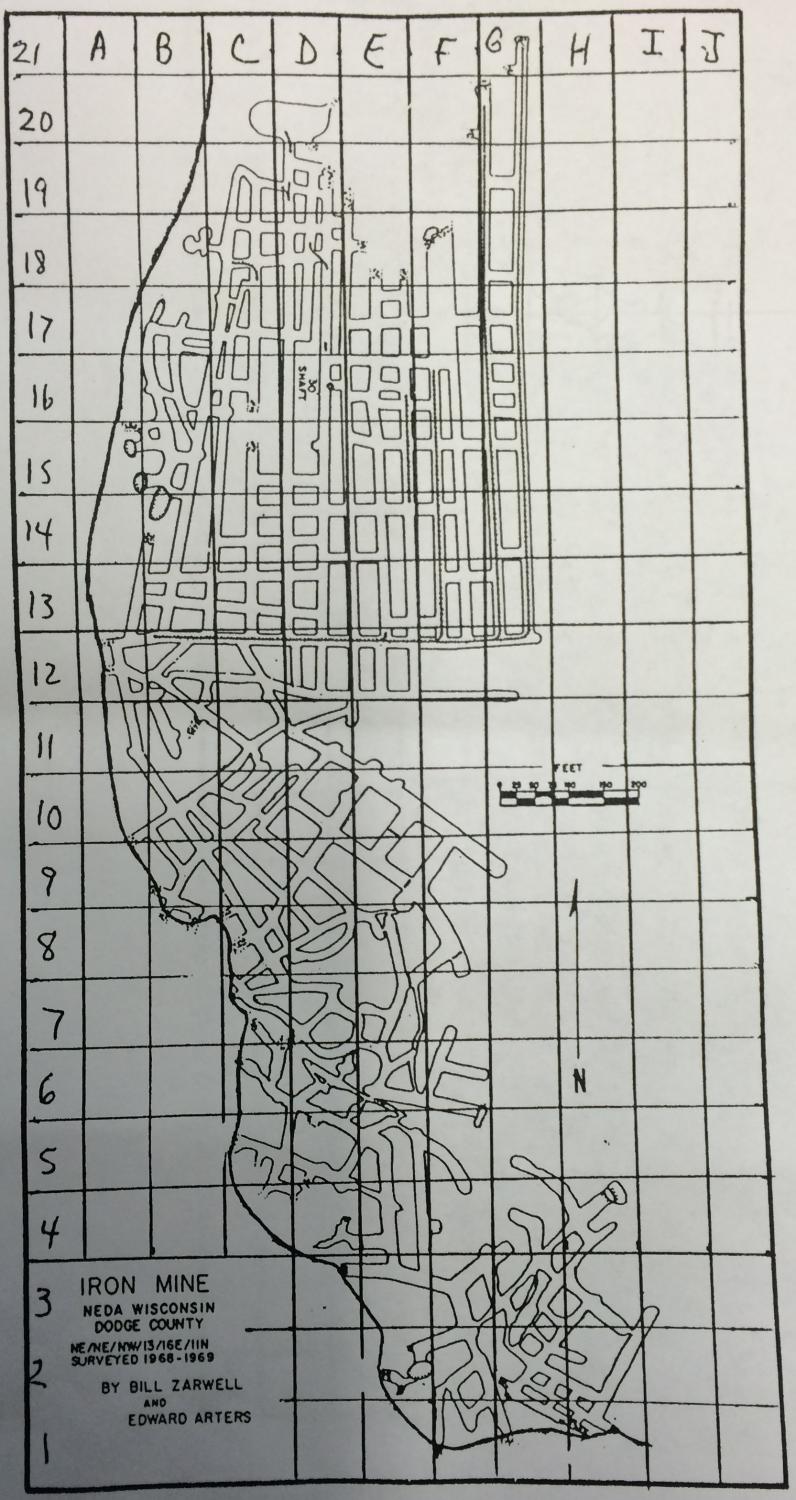

The Interior search team was assigned to the north end, a grid-like pattern of shafts. After an unsuccessful search there, rescuers moved to the southern portion, a much more challenging network of mine shafts likened to “a bowl of spaghetti.”

Rescuers also confronted areas of water inside the mine, some measuring six to eight feet deep. Using a canoe stored there by scientists, rescuers paddled across the area to reach solid ground.

Having searched the mine for about two and a half hours, the HURT was ready for rehab. Calls were placed to the Milwaukee Fire Department’s Heavy Urban Rescue Team, and Jennifer Redell, a conservation biologist and cave expert with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR), was also on her way.

There Had To Be Another Way

The unsuccessful searches of the north and south ends of the mine had rescuers stumped. They’d come into the mine through all the obvious entryways. Could there be another entrance?

Just as they paused the consider the possibilities, the father of one of the boys approached the Exterior search team. There was an additional entrance, located just beneath a cliff, that he thought the team should check.

“We were kind of looking over (the cliff), and the dad looked at me and said, ‘Well are you going to go down there or am I going to go down there?’” Fredrickson remembers.

There was no question: The team was prepared to go. As Fredrickson and his team advanced into the tunnel, the scene was worrisome.

“It was very rugged, and it looked like it had recently collapsed,” he described. “The ceiling looked very unstable.”

What’s more, it appeared there wasn’t much to explore beyond a large pile of rubble situated not too far from the entrance. But the HURT is nothing if not tenacious and thorough! They wanted to be certain the tunnel was clear before moving on.

Fredrickson climbed over the rubble and shined his flashlight into the cave. There he discovered a tunnel extending “as far as you could see.”

Firefighter/Paramedic Adam Phillipson joined Fredrickson inside. As they advanced, the tunnel narrowed into a two-foot-wide chute. Jagged, broken rocks beneath their feet added to the challenges.

“It forced me to move slowly,” said Phillipson.

That’s when he made a game-changing discovery.

“I looked down to where I was going to step to make sure the ground was stable, and there was a perfect imprint of a tennis shoe in the mud in front of me,” he said.

Proceeding a bit further, he also noted the imprint of fabric resembling denim in the mud on the rocks. While this was a breakthrough in the search for the missing boys, it also called to mind more questions than answers.

“A lot of thoughts are going through your head,” said Fredrickson. “Are they under this pile of rubble? Are they deeper in the cave? Did this collapse and they couldn't get out so they went further in?”

The team advanced as far as they felt they could safely go. Then it was decided they would come back out and strategize once again before re-entering.

The Discovery

The Milwaukee HURT arrived in Iron Ridge at about 10:30 a.m., and DNR expert Redell was right there with them. They teamed up with Phillipson, who escorted them back into the tunnel where the footprints were discovered.

After directing Milwaukee HURT to the point where he’d left off, Phillipson waited outside with his crew for updates from the Milwaukee search team.

“It felt like five minutes later they came out and there were the three little boys with them!” said Fredrickson with a smile. “It was a very happy and rewarding time.”

The boys were unaware of the amount of attention they’d acquired while inside the cave. They’d also just spent several hours in 40-degree temperatures wearing warm-weather attire. Paramedics made sure they weren’t hypothermic or suffering from any other ailments, and rescuers did their best to ease the boys’ quick transition back to their normal life.

“We told them that their parents were down there waiting for them, that they’re going to get a lot of hugs and kisses, and then… probably be in big trouble!” Lt. Ryan Stebnitz said with a chuckle.

Gaining Perspective

With the rescue over and the boys happily reunited with their families, everybody finally had a chance to take stock of all that had happened. Reflecting on the operation, it occurred to rescuers that they were on the verge of a close call.

During their search for the missing boys, Milwaukee HURT said they and Redell had advanced as far as they possibly could inside the tunnel where the shoe prints were found. Reaching the end of the road with no other sign of the boys inside, they turned around to come back out and declare the tunnel cleared.

As the search team made their way back toward the cave entrance, the boys happened to wake up and see the beam of the rescuers’ flashlight bouncing around in the cave. The boys called out for help. Rescuers didn’t hear them at first, but as they advanced closer and closer, they realized the boys had been right there the entire time.

It was extremely lucky timing.

“If we had left that cave, we would have marked it. That would have been our secondary search, and we never would have gone back,” said Fredrickson. “If they would have kept sleeping, we might not have ever seen them again.”

A Success Built On Teamwork

A vast amount of collaboration went into this operation, and it involved a combination of departments that had never worked or even trained together before.

What began as a local law enforcement response grew to include local fire departments and ultimately blossomed into a large-scale search and rescue operation involving regional response teams, MABAS, the Wisconsin DNR, Wisconsin Emergency Management, and others.

Jason Boeck, chief of the Iron Ridge Fire Department and a sergeant with the Dodge County Sheriff’s Office, was the incident commander overseeing the entire operation.

“The guy was awesome. He did a great job,” said Madison Fire Lt. Stebnitz.

Firefighter Josh Balli added, “It was all a giant team effort, and it worked pretty flawlessly.”

About the Heavy Urban Rescue Team

The Madison HURT was established in 2007 as a continuation of an investment in technical rescue capabilities that began in 1985. Although it never trained on mine rescue, its training in confined space rescue and trench collapse were instrumental in the Neda Mine operation. This team consists of 57 total members and is based out of Madison Fire Station No. 8 on Lien Road.

Pictured below are some of the rescuers involved in the Neda Mine operation: (L-R) Firefighter Arthur Dinkins, Firefighter Michael O'Connell, Firefighter Cory Hesseling, Acting Lieutenant Eric Fredrickson (search leader), Lt. Ryan Stebnitz, Firefighter Josh Balli, and Firefighter/Paramedic Kevin McDonald.

Not pictured: Asst. Chief Clay Christenson (search command), Firefighter/Paramedic Adam Phillipson, AE Wade Raddatz, and Firefighter Richard Scott.

.jpg)

† Schmidt, G., Boeck, J., Christenson, C., Votsis, D., McNulty, B. (2017). MABAS-WISCONSIN in ACTION, 8(2), 1-11. http://www.mabaswisconsin.org/pdf-documents/NewsletterVol8Issue2.pdf