Why add chlorine? The story behind water disinfection

posted

"...one kid every 8 seconds is dying because a simple thing like chlorination of drinking water is not there."

-Dr. Marty Kanarek, UW Madison

----

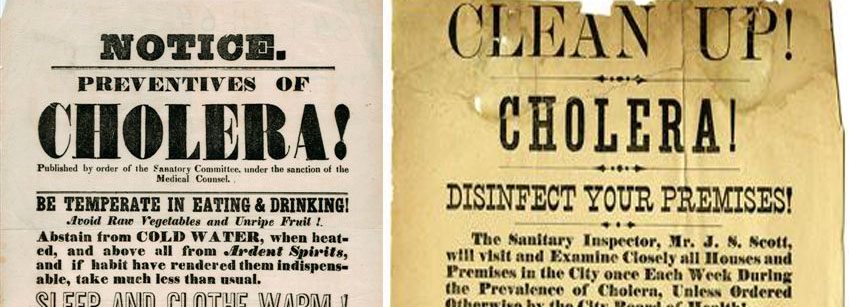

It's a bleak picture: frequent outbreaks of cholera, typhoid fever and dysentery; children routinely dying before their 5th birthdays; adults lucky to live past age 40. UW Madison environmental epidemiologist and population health sciences professor Dr. Marty Kanarek insists it's a very real picture of what life used to be like in the United States. According to FEMA, the 1849-51 Midwest Cholera Epidemic alone claimed more than 11,000 lives, making it the 7th deadliest disaster in U.S. history. Outbreaks would continue in communities across the country for decades, until one city changed everything. In 1908, Jersey City, N. J., began adding small amounts of chlorine to its drinking water. The practice of drinking water disinfection quickly spread, and suddenly the picture of public health in the U.S. started to change.

"Having clean drinking water is one of the reasons we, in countries like the United States, live long, happy lives. Chlorination is crucial to having a safe, modern civilization," Kanarek says. "If we stopped, and when places have stopped, people get sick and die."

Kanarek points out that much of the world is still living in that bleak, pre-1908 reality.

"At least a third of the world doesn't have safe drinking water – over a billion people. In those places, it's estimated about 3 million children under five years old die per year from diarrhea, from drinking water that has infectious agents in it. It's like one kid every 8 seconds is dying because a simple thing like chlorination of drinking water is not there."

Children in a remote Guatemalan village wash in chlorinated water thanks to a system built by

Wisconsin Water for the World.

Risks of chlorination

Kanarek's ardent support of drinking water chlorination may seem surprising, considering that three decades ago, he was one of the first researchers to look at its possible harmful side-effects. Kanarek and other researchers worked with the EPA to examine potential health risks of long-term exposure to chemicals known as disinfection byproducts, which are formed when chlorine interacts with organic matter in raw water. They found that people who drank water containing high amounts of disinfection byproducts over many years had an increased risk of cancer.

But Kanarek has a strong message for people who are now fearful of chlorinated water in the wake of the EPA's investigation.

"None of those investigators would say that we should stop drinking water chlorination. (We) found a potential cancer side-effect of chlorinating our drinking water. But that is a tiny potential effect as compared to the overwhelming good of protecting me and everybody else from getting cholera, typhoid, E. coli," he says, pointing out that since the study was conducted, the EPA has worked with utilities to limit disinfection byproducts in drinking water. "Now water districts are controlling that by not over-chlorinating. They have a middle ground between enough chlorination to stop the infectious disease, but not enough to have excessive amounts of these chlorination byproducts that people worry about."

The City of Madison has been adding a small amount of chlorine to its water since 1927. Madison Water Utility water quality manager Joe Grande says when it comes to disinfection byproducts, Madison's levels are far below what the EPA considers concerning.

"We depend on groundwater that's been naturally filtered, so a lot of that organic material that reacts to form disinfection byproducts is already removed."

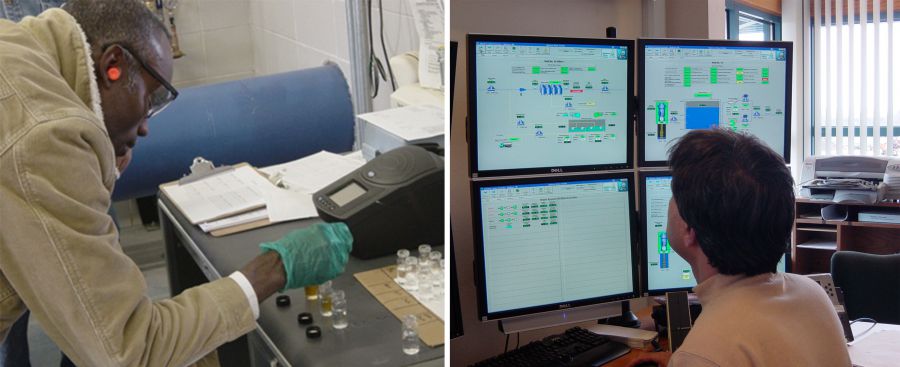

Grande admits that there are other ways to disinfect drinking water, like UV radiation or ozone gas. But those methods are not only much more expensive than chlorination, they also fail to protect the water after it leaves the treatment plant and heads through hundreds of miles of pipeline to people's homes. Chlorine offers what's known as a "residual" – enough stays in the water to continue to protect it from bacteria and viruses until it reaches the tap. Madison Water Utility performs thousands of tests every year at wells, reservoirs, schools and businesses across the city, always checking to make sure a small amount of chlorine is still present.

Chlorine levels are monitored through hands-on testing at Madison wells and by remote sensors

"It would be nice if there was a test where we had a dipstick, and we could just stick it in the water and it would say 'safe' or 'unsafe.' There's no test for that. The best thing that we have is a coliform test, which is a general indicator of what might be in the water. And the shortest coliform tests take 18 hours, most take 24 hours," Grande says. "So I can't go out to a source and confirm that the water is safe at any given moment. What I can do is I can go out to that location and confirm that we do have a chlorine residual. If we do, I'm very confident that that water is safe. There's no other test that we're doing more frequently."

Chlorine levels are also checked by sensors and monitored remotely by a Madison Water Utility pump operator 24 hours a day.

"If the level of chlorine is below a certain limit leaving the well, (the operators) shut down the well. They've got 15 minutes to do that. So we take it very seriously."

Understanding the science

Although Grande refers to the occasionally-noticeable presence of chlorine in Madison's water as "the smell and taste of safety," not everyone sees it that way. It's easy to find websites, particularly those that sell home water filtration systems, warning of a long list of possible chlorine risks – everything from cancer, to food allergies, to hair loss, asthma and acne.

Kanarek hopes most people will take all the claims with a grain of salt, because he says the research that's been done on chlorine doesn't support the fears.

"Anybody who says we shouldn't chlorinate our drinking water just doesn't know the science. Maybe we haven't done a good enough education job publicly – in the newspapers, on the radio and T.V. – about how important chlorination is and how a lot of the world really needs it."

Kanarek says he's appalled at the recent online backlash against drinking water chlorination, but he's not surprised. He believes education is the key to understanding what he calls one of the primary tenants of modern public health, one he insists we cannot risk taking for granted.

"On the internet people start saying things and people start believing it. I teach at a great university where we're trying to educate all the students that leave here about these basic things. So I'm not surprised that these kinds of things take off for a while. But it'll fade away because drinking water chlorination is so crucial."