When winter's over: the lasting impact of road salt

posted

(For more information on the impact of road salt in Wisconsin and what you can do to help, head to www.WiSaltWise.com.)

"Ominous trend"

More than two weeks after the last major snowfall in Madison, tiny white crystals still dot University Avenue -- remnants of 140 tons of road salt dumped on the two mile-long stretch between Segoe Rd. and Allen Blvd. over the winter. By summer, it will all be gone. But where does it go? It's a question Madison Water Utility water quality manager Joe Grande says more people should be asking.

"It goes into the lake. It finds its way into groundwater," Grande says. "We want our streets cleared, but we don't think about the impact that it has."

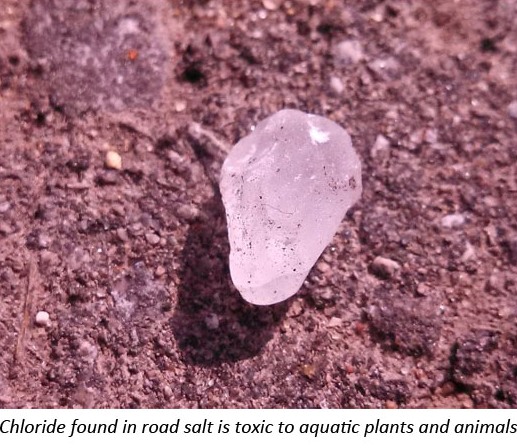

The impact on Madison's drinking water is becoming hard to ignore. Road salt is made up of two chemicals, sodium and chloride. Both are now showing up in water pumped from a municipal well located near University Ave. and Whitney Way.

"We've seen a pretty ominous trend...chloride levels there have doubled in the last 15 years," Grande says, adding that sodium levels at the well are already "above the threshold" for people on salt-restricted diets.

While high chloride levels don't necessarily pose a health risk, they can give the water a salty taste. Grande says that if nothing is done to cut down on road salt use in the area, people who get water from the well may eventually deem it unfit to drink.

"In another 10 or 15 years, they're going to start--if they haven't already--noticing a difference in taste. If we don't do something now, it's going to require treatment or considering abandoning that well," Grande insists. "Treatment options would include some type of distillation or reverse osmosis that would be incredibly expensive, energy intensive, and wasteful in terms of the reject water associated with them."

Abandoning the well would be even more difficult because it supplies 800 million gallons of drinking water every year.

"It's a pretty important supply point for our system. You don't easily make up 800 million gallons of water," he says.

Optimism in short supply

For most wells in Madison, the water utility has developed individualized wellhead protection plans meant to protect the groundwater that supplies those wells from contamination. Using information from the plans, city leaders pass ordinances limiting what types of businesses and industry can locate in protected areas near a well. But even though a section of University Ave. lies within one of those wellhead protection zones, there has never been an effort to limit road salt use there. Grande wants that to change.

"We definitely need to do something...We have data from three monitoring wells at University Crossing that show really high levels of chloride in the groundwater, in the range of 300 to700 milligrams per liter. That's right at the top of the water table. Groundwater should have less than 10 milligrams per liter of chloride."

Grande is working with local leaders and environmental groups in hopes of curbing salt use on the two mile stretch of University Ave. between Segoe Rd. and Allen Boulevard. But because the road is technically part of the state highway system and is maintained by Dane County, the plan would mean an enormous amount of cooperation not just from City Streets, but also from the DOT and Dane County Public Works.

It would also mean buy-in from the thousands of commuters who use University Ave. every day as a major route into the city. Limiting salt on the heavily used four-lane highway could affect everything from commute times to traffic congestion on nearby streets to public safety. Convincing drivers to slow down and exercise a lot of patience for the good of our water supply is a tall order, and Grande isn't optimistic that the public is ready give up the convenience that heavy road salt use provides.

"It certainly is a larger conversation about what our expectations are as a community in terms of travel in the winter time...There are a lot of city leaders that support going in this direction, but there's going to be pushback from the general public and commuters who are using this stretch of highway who don't consume the water."

Reduced salt area?

While restricting salt use on a major highway may be unheard of in Wisconsin, it's common practice on the east coast. States like Massachusetts and Vermont actively work to protect watersheds and groundwater by designating "reduced salt" zones on roadways and posting signs warning drivers.

Grande hopes that soon Madison will follow their lead, not just to protect the well near University Ave., but to protect our lakes and streams, where he says the impact of road salt will eventually be devastating.

"It's a bigger lakes issue, quite frankly. In Lake Wingra, for example, it's starting to have a noticeable effect on the various plant species and animal species, in particular some of the macro invertebrates, the larvae and insects and those types of organisms that are the base of the food chain."

In a 2010 Wisconsin Natural Resources Magazine article, DNR water resources specialist Roger Bannerman painted a bleak picture of Wisconsin's future if we don't get our salt use under control.

"Road salt use is a sleeping giant," said Bannerman. "The potential for chloride to damage our water systems is more inevitable than climate change."

Bannerman added that driving expectations in the winter need to change.

"Keeping our roads safe for driving by using more and more road salt is not sustainable. At some point the benefits of driving during severe weather conditions might be outweighed by the damage to our lakes, streams and groundwater."

That damage is likely already happening across Wisconsin. A study from the US Geological Survey released in 2010 found that all streams monitored in south-central and northern Wisconsin during the winter had chloride levels that exceeded the EPA's chronic water quality criteria. The results surprised even researchers.And it's not just Madison. Damage to our ecosystem because of road salt is likely already happening across Wisconsin. A study from the US Geological Survey released in 2010 found that all streams monitored in south-central and northern Wisconsin during the winter had chloride levels that exceeded the EPA's chronic water quality criteria. The results surprised even researchers.

"We expected to see elevated chloride levels in streams near northern cities during the winter months," said Steve Corsi of the USGS Wisconsin Water Science Center when the study was released. "The surprise was the number of streams exceeding toxic levels and how high the concentrations were."

Some streams had chloride concentrations higher than 860 milligrams per liter, far above levels toxic to small aquatic life.

But even though the danger to our waterways from road salt is clear, the way forward isn't so simple. Grande says we must find a balance when it comes to public safety, convenience and our duty to protect Madison's environment for future generations. He believes that short of a major public outcry, little will change. And so far, that outcry isn't coming.

"These are larger societal issue questions about what we want and at what cost. And then the question always comes, who bears the cost? The environment bears the cost, and the citizens of Madison will someday."