EPA seeks details of Madison’s Lead Service Replacement Program

posted

Madison's once-controversial program may now become a model for other cities

---

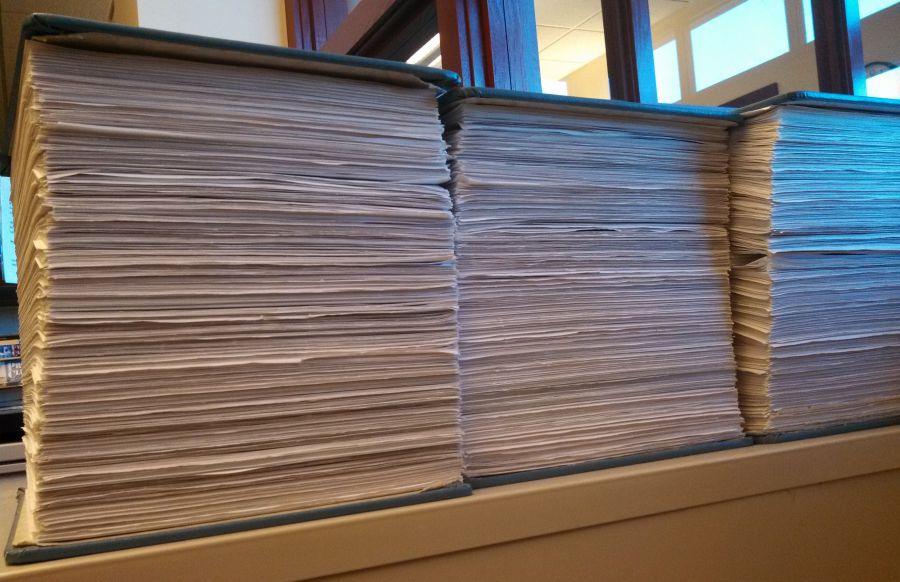

“Those books are the lead service contracts,” says Madison Water Utility operations clerk Amy Jones, gesturing over her shoulder to three massive binders stacked neatly on top of a filing cabinet.

The binders contain more than 8,000 contracts, one for every Madison homeowner who replaced their lead service line, the pipe that leads from a water main to a home. In Madison, the practice of using lead pipes for water services wasn’t discontinued until 1928.

“Nobody in this day and age wants to have a lead service,” says Jones. “People who are thinking about buying a house will call and ask if (the service) is lead.”

Thousands of lead service replacement contracts filed by Madison homeowners

But chances are it won’t be. That’s because of the utility’s Lead Service Replacement Program, which was largely completed in 2011. On the surface, the program sounds like a resounding success. In a little more than a decade, the city replaced nearly all of its lead services, bringing safer water to thousands of people living in older homes. Except that success almost didn’t happen at all.

“I and other people at Madison Water Utility have made national presentations. We’ve made sure that everybody knows Madison’s experience,” say chemist and independent consultant Abigail Cantor, P.E.

The experience, Cantor says, wasn’t an easy one. Now, three years after its completion, Madison’s Lead Service Replacement Program is drawing the attention of the EPA. The agency, which oversees drinking water regulations, is taking a hard look at how Madison undertook the enormous and unlikely task of replacing thousands lead pipes – pipes that were technically private property.

Testing Madison's water

The battle to get the lead out of Madison’s water started in 1991 with the passage of the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule, which required utilities to test drinking water inside older homes for lead. Although the rule is a federal law, it’s enforced on the local level by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

In 1992, Madison ran its first round of tests under the new rule, and the results weren’t good news. Elevated lead levels found in some of the homes meant the city had exceeded the EPA's action level for lead and would be required to bring those levels down.

“Madison was told that they need to optimize the lead in their water by getting (it) down to 5 parts per billion,” recalls Cantor, who was working for a consulting firm at the time. “Madison wanted to do some studies, and I got assigned to do this.”

.jpg)

Cantor conducted pipe loop studies to test the effects of chemicals in Madison's water

It was common knowledge in the water industry that lead services could corrode, causing the dangerous heavy metal to show up in a home’s drinking water. What wasn’t common knowledge was exactly how to prevent it. Most water utilities turned to chemicals.

“The Lead and Copper Rule is written as if lead in the water is a real simple thing. If you’re over the action level, simply put in a chemical and you’ll be fine. And that’s the way it still is today,” explains Cantor. “I did some studies of Madison’s water system to find a chemical that could be put in the water to control the lead. As far as anybody knew, that’s what you do. You’ve got to alter the chemistry of the water so that the lead stops going in.”

But Cantor says Madison soon found itself in a position where the simple answer wasn’t the answer at all.

“I ran all these tests using the chemicals that are prescribed by the rule … One of (the chemicals) increased the lead four times the amount of untreated water! I thought, ‘Something’s not right here. Everybody’s using this chemical and yet it can increase the level of lead.’”

One of the most common additives to control lead corrosion is phosphoric acid, but in Madison, that chemical was off the table because of growing concern over phosphorous contaminating area lakes and watersheds. So the city was left with just one option.

“Everything pointed to removing the lead service lines,” says Cantor, who reported her findings to Madison Water Utility in 1994.

“They said, ‘Okay, we’ve got to talk to the DNR.’ Basically the Lead and Copper Rule says you must put some kind of chemical in the water first. Because you’ve done a study offline, it’s not going to count. Then came years and years of discussion with the DNR about how Madison’ could skip the step of putting a chemical in the water.”

More than four years later, the DNR finally relented. Madison Water Utility would be allowed to skip trying out phosphoric acid in the water supply and could move straight to lead service replacement. But that part would be the toughest of all.

The public pushes back

It sounds simple: replace all the lead service lines in the city of Madison and solve the lead problem once and for all. But it wasn’t so simple, largely because of property lines.

“The water service lines to people’s homes are owned by the utility up to a certain point. It’s up to the property line,” explains Cantor. “And on the property line, there’s this little valve – it’s called a curb stop. The utility can do anything they want with that. But from the curb stop to the house, it’s the property owner.”

The utility had already begun replacing water services on its side of the valve, but if the rest of the pipe was still made of lead, there was little hope that it would make a difference when it came to lead levels inside the home.

“We knew that the lead service line was the source of the lead. Until you remove the (entire) lead service, you’re still going to have an ongoing source of lead,” says Joe Grande, water quality manager with the utility.

So Madison Water Utility needed action from the Common Council. An ordinance would be necessary to require thousands of homeowners to replace lead services on their sides as well. To lessen the financial burden for homeowners, the utility would pay for half the cost of replacement up to $1,000. Money for property owner reimbursements would come from antenna revenue – money the utility receives by providing space on its water towers for cellular antennas.

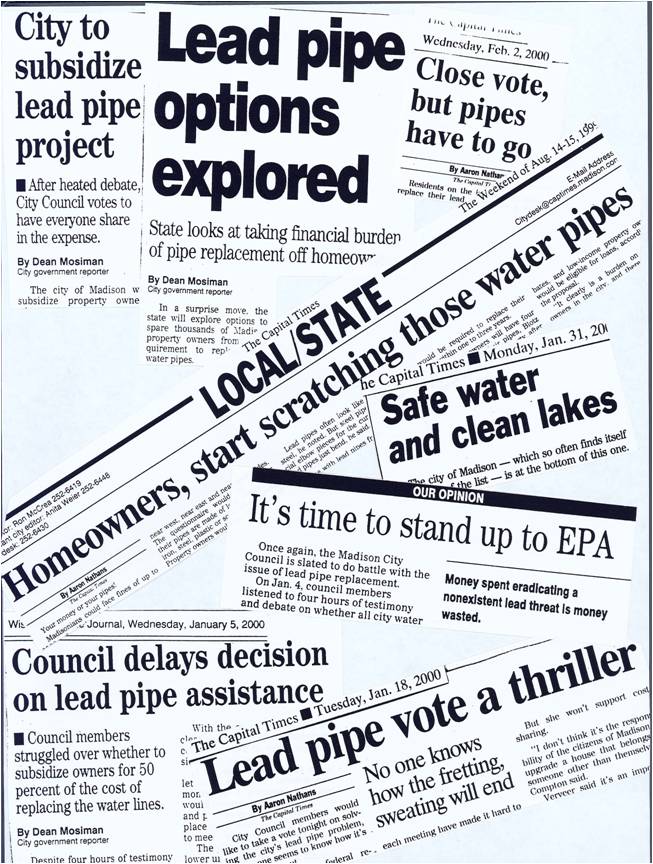

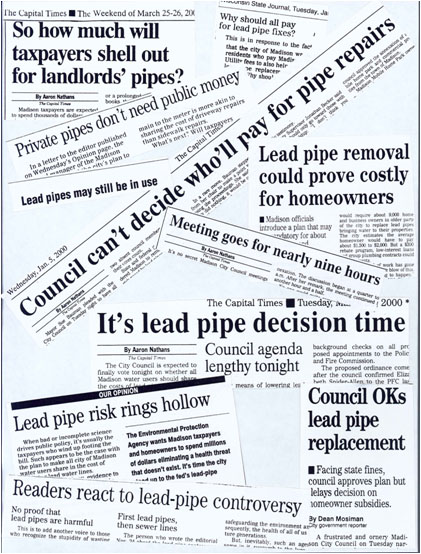

The proposal was instantly met with criticism. Not only did many Madisonians feel that public money shouldn’t be used to pay for private pipes, some didn’t believe that a real public health risk from lead services existed at all. Underscoring that belief was an opinion piece from the Wisconsin State Journal that ran days before the Council vote, with the headline, “Lead risk rings hollow.”

“It’s fascinating. I’m mystified,” says Cantor of the negative reaction. “First of all, it’s a federal law. Basically Madison had to comply. But the second thing is, if I had a lead service line, I would get it out so fast! And here was an opportunity to be subsidized to get it out.”

But Grande isn’t as surprised at the pushback.

“Lead is not something that you can see. You can’t taste it. You can’t smell it. It’s this kind of hidden contaminant,” he explains. “People will say, ‘I’ve lived in this home for 50 years. It’s not something that’s affected my health … This is a waste of money.’ I think that played into it.”

Madison Water Utility employee feeds new water service pipe in front of a Madison home

“A huge success”

In the winter of 2000, after months of wrangling over how it would work, the Common Council narrowly green lit Madison Water Utility’s Lead Service Replacement Program, the first of its kind in the country. The seemingly impossible step of replacing 8,000 lead water lines was now underway. By the end of 2012, it would be one of the crowning achievements of the utility.

“Certainly it’s something to be very proud of,” says Grande. His department still regularly tests for lead in Madison’s water, but he’s not worried about complying with the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule anymore. According to Grande, the problem of lead in drinking water has been almost completely eliminated in Madison because of the program. It’s something few other cities can say.

“It’s a huge success. Knowing that lead service lines are the principal source of lead in drinking water and doing what you can to remove lead services …We are light years ahead of other utilities that have decided to do the corrosion control chemicals, which they’ll do forever until they do replace the lead services.”

Now, as the EPA considers revising its Lead and Copper Rule for the first time, Madison is one of a handful of cities that they’re looking to for information that might someday help others dealing with lead.

“Now we know what the costs were. We know what some of the hurdles were. But we also know what the positive outcomes are,” says Grande, who insists that despite those hurdles, the city made the right decision.

“It was something the utility and the city decided was an important thing to do. In the end, I think this is where utilities are going to be pushed. There’s a growing concern in the regulatory industry and the drinking water industry in general that we’ve been talking about lead for two decades now, and little has happened from a lot of people’s perspective. In Madison, that’s different. We made the decision, we went forward and we did it.”