Wisconsin Water for the World: Making a difference one village at a time

posted

At first glance, they couldn't seem more different from Wisconsin. The tiny villages of Nueva Providencia, El Adelanto, Sacbochol, El Rosaria, Tierra Linda, and Pujujilito are tucked into lush Guatemalan mountainsides some 2,700 miles south of the Badger State. But there is one thing that connects them to Wisconsin – water.

"It's turned into a passion for me. It's changed me," says Kenosha Water Utility employee John Andersen, who's spent the past six years working to bring safe drinking water to some of the remotest areas of Guatemala, one village at a time.

"My first trip in 2008, I was on the airplane ride going down there and thinking, 'Wow, this is a once in a lifetime thing.'

But it turned out, once in a lifetime wasn't enough.

"I was very moved, very touched by how a small group of people can affect a whole village and do something positive. So I said to myself on the way home, 'I want to continue to do this as long as I can.'

Andersen took that first trip as part of a group called Wisconsin Water for the World, founded by the Wisconsin Water Association in 2007. He now serves as its chair, each year bringing together water professionals from across the state to design and build sustainable drinking water systems in Guatemala. Like the villages it serves, Wisconsin Water for the World is pretty small – there's no head office, no branches in other states – just a group of Wisconsinites who want to use their professional skills to make a difference.

"We don't have any overhead; all of our people are volunteers and in the water profession," Anderson says. "We'll help design a system, and then raise the funds, and come down for two weeks and put it in."

And he doesn't usually have any problem finding people ready to donate their time and expertise. Ben Wood, an engineering consultant based in Milwaukee, traveled to Guatemala in 2007 and says the work gets to the core of the reason he chose a career in water in the first place.

"One reason I got into the drinking water industry was to do something that had a deeper meaning for me, to be able to work in one form or another toward one of life's essential needs," he says.

"No looking back"

For most people born and raised in the United States, it's unimaginable. No running water. No electricity. But until two months ago, it was all the 30 families living in Pujujilito, Guatemala, had ever known. Andersen says in many villages like Pujujilito, the lack of accessible water can be hardest on the women.

"They're the ones tasked with getting water manually. And it's not just run down one or two blocks away. They spend four and five hours a day going to get water."

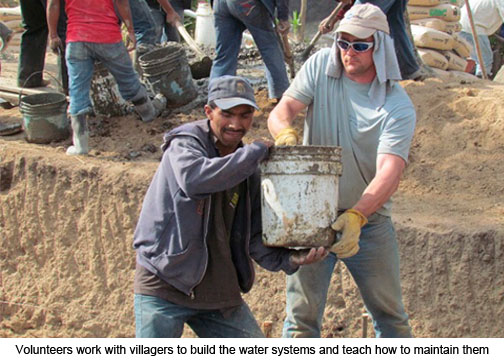

In March, more than a dozen volunteers from Wisconsin made the long journey to Pujujilito to build a sustainable drinking water system. But long before their arrival, the people who live there began preparing.

"The village sets up a Water Committee, which will watch over the system and learn how to maintain it," explains Andersen, adding that a local non-governmental organization called Agua Para La Salud (Water for the World) does much of the groundwork, reaching out to villagers and arranging for supplies before the implementation team from Wisconsin arrives.

Plenty of preparation happens in Wisconsin as well. Wood, now vice chair of Wisconsin Water for the World, is a member of the group's engineering subcommittee which reviews survey information and designs the systems that implementation teams will build on site.

"At the end of that two week trip, when (they) turn the pump on, there's really no looking back for that village," Wood says.

During their two week trip to Pujujilito, Wisconsin Water for the World volunteers worked closely with villagers to build a pump house and a 10,000 liter tank that captures water from a natural mountain spring. That tank was then connected to another above the village and piping was installed from it to each of Pujujilito's 30 homes. The system is meant to last a quarter century or more.

"It's a huge change for everyone in the village because now there's accessible water," Andersen says. "Sustainability is the key."

From the village to the classroom

Volunteers from Wisconsin weren't alone on their journey to Guatemala. School kids from 27 classrooms across the country were right there with them, connected via satellite modem and live web cam. The remote classroom sessions are part of an offshoot program Andersen created called Adventure Kids Learning, which uses Wisconsin Water for the World's projects as a teaching tool.

"So many kids get exposed to this small group of Wisconsin professionals in the water industry through Adventure Kids Learning," Andersen says."Kids are seeing this stuff in the classroom. That personal connection just goes a lot farther than we ever thought it would."

The biggest take away for children who follow the trips: learning to value what we have here.

"To us, it's not even a thought. We don't even think about water," says Wood. "It's just so taken for granted."

But Andersen knows one Milwaukee 3rd grade class that probably doesn't take it for granted anymore.

"This year the teacher had her students carry around water. When they went to music class, they went to lunch, they went to wherever – they had to carry these 2-gallon bottles around. These kids really got it, they really understood because they were carrying this stuff around. They connected with us (via satellite), and we had a great talk from down there to them. And then when it was over, the teacher says, 'Okay, we can get rid of the water now. Let's bring the bottles over to the sink.' And one of the kids goes, 'No, we can't just waste it and put it down the sink. Let's use it for something!' It was really cool to hear that."

Andersen is already looking for more classrooms to bring into the fold for next year's trip because even though Wisconsin Water for the World is small, he knows its impact can be enormous.

"There's a ripple effect with us having a personal connection," he says. "It's powerful."

On Saturday May 10th, Madison Water Utility will hold its first ever Chocolate/Coffee tasting fundraiser to help Wisconsin Water for the World build sustainable drinking water systems in Guatemala. The event will feature local chocolates and treats, as well as fair-trade coffee grown near Pujujilito in the Solola region of Guatemala. $10 donation required.